Justice was sometimes meted out in an arbitrary and indiscriminate fashion, or so it seemed in October 1899 when Fred Mason was given a five-year sentence to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Jewelry and “trinkets” belonging to a white man, J. M. Golledge, were apparently found in Fred’s possession. He claimed the actual thief was a man named George Carpenter however he pleaded guilty to burglary. He was probably hoping that, given his youth, Judge Townsend of Chickasha, Indian Territory, would be lenient. Clearly Fred misjudged the judge.

Fred arrived at Leavenworth on October 9, 1899. He was 16-years-old, 5 foot 6 inches tall and weighed 130 pounds. Born in Texas, Fred had no education and left home at the age of 12. Prior to prison he worked as a hotel waiter and a bootblack.

During his year and a half stay at Leavenworth he was put into solitary confinement 11 times for talking (which was never allowed), laughing, using foul language, marching out of step and loafing when he was supposed to be working. Given that Leavenworth housed some of the hardest criminals in America, it’s impossible not to wonder if Fred’s tendency to break the rules wasn’t actually a desperate attempt to get himself removed from the rest of the inmate population and, consequently, out of harm’s way.

Fred’s last stay in solitary lasted almost a month, from December 19, 1900, to January 17, 1901. It’s likely that shortly after he got out of solitary he was moved to the hospital because Fred had a serious case of tuberculosis. In fact it’s almost certain that at times when the guards claimed he was avoiding his tasks he was actually too weak to work.

On April 6, 1901, Fred Mason died at the Leavenworth Prison Hospital. His cause of death was listed as “tabes mesenterica,” which, in layman’s terms, means he literally wasted away. An autopsy found that tuberculosis lesions were spread throughout his abdomen — he had probably been unable to eat for weeks, maybe months. His heart was described as “small and flabby” and his aortic valve was narrowed, probably also a result of his tuberculosis.

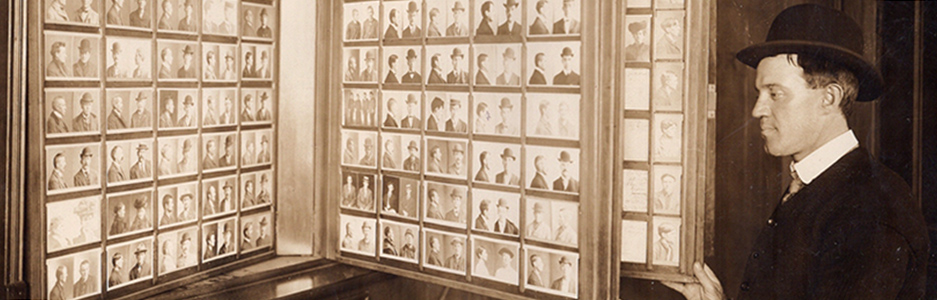

The Leavenworth warden, Robert W. McClaughry, told Fred’s mother that her son suffered shortness of breath and had gone deaf before he died. Perhaps trying to ease a mother’s grief over the loss of her only son, he also noted that Fred “did not suffer much pain.” McClaughry had arrived at Leavenworth just three months before Fred Mason became an inmate. A reformer in the field of penal correction, the 60-year-old McClaughry believed that prisons could work to improve their inmate’s lives, not simply punish them. He also introduced Bertillon’s system of cataloging suspects and criminals into the United States and it’s likely that McClaughry initiated the process of taking inmate photos at Leavenworth.

McClaughry was writing to Fred’s mother, in part, because he needed to know what the family wanted done with the body. Rutha Mason wrote back, thanking McClaughry for letting her know right away that her only son had died and for his “kindness to Fred.” She wanted to know if Fred had left any final words for his family. McClaughry wrote back to say that he had been unconscious for three days prior to his death and had been unable to speak.

The Mason family was too poor to afford to have their son’s body returned to Texas, so his mother requested that prison officials “bury Freddie there.” She mentioned that she had made every effort possible to get him a pardon but had been unsuccessful. The warden reassured her that her son’s grave would be marked with a “neat headstone, so that if any time his friends desire to remove his remains, they can be identified and obtained.”

Currently Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary maintains a cemetery for prisoners but it is not accessible to the public nor does it contain any headstones.

Featured photo: Fred Mason, Leavenworth Penitentiary Inmate Photograph, 1899. Collection of NARA-Kansas city.