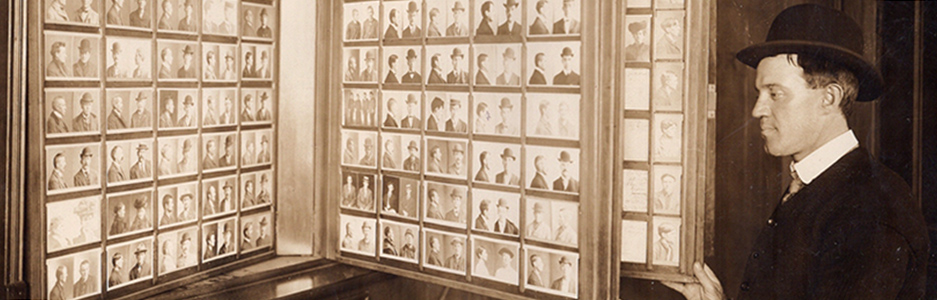

Mug shots have been in the news a lot lately, thanks to Donald Trump, the first American president to pose in front of a police camera.

It got me thinking: What was the first mug shot ever taken?

According to multiple online sources, a photo taken in Birmingham, England was among the first mug shot ever made. A collodion positive (called an “ambrotype” in America), the photo is in the collection of the West Midlands Police Museum. (Full disclosure: I have not seen the photo in person.) The claim is based on a date, 1-3-53 (March 1, 1853), written on a piece of paper stuck to the back of the photo.

I am skeptical of the claim. Frederick Scott Archer, an Englishman, developed the collodion process in 1849. He published a “how-to” manual in 1852. One year would have been very fast for the technique to become available commercially. But it’s possible that a few photo studios in big cities like Birmingham were making collodion positives by 1853.

What else could help with dating the photo? I think we need to know more about the man in it. Fortunately his name—Isaac Ellery—was also written on the paper attached to the back.

Mug shot of Isaac Ellery, showing the back (right) and front (left) of the photograph. West Midlands Police Museum

So who was Isaac Ellery? You can be forgiven if you thought he was some sort of master criminal, because it’s “The First Mug Shot” for heaven’s sake! But no, he was not a big-time crook.

Here is what my eyes tell me: Isaac cared about his appearance. Although his clothing is worn-looking, he’s reasonably well dressed. He’s sporting what we now called a “Dutch Beard” — a beard that took effort to maintain in the era before safety razors.

He chose to look away from the camera. That makes me think he felt ashamed at being photographed. But then again, he’s smiling ever so slightly, so maybe not. With an intense, brooding look under heavy brows, he’s handsome in a rough sort of way. I can imagine him playing Edward Rochester in a BBC version of Jane Eyre.

But unlike the master of Thornfield Hall in Charlotte Brontë’s novel, Isaac was a poor man.

His parents, Abel and Hannah, were honest, hard-working farmers who were married for 42 years. Isaac, their fourth child and second son, was born in 1832 in the hamlet of Didcot in Beckford, Gloucestershire.

Farming the land of wealthy men was the way of life for most people in rural Victorian England. As a young married man, Abel toiled as an agricultural laborer, eventually working his way up to the managerial position of “farm bailiff.” Isaac and his brothers all worked as farm laborers.

Isaac first drew the attention of authorities when he was accused of theft from his master in January 1852. (No details of that crime have survived). This was such a common accusation that there was actually a legal term for it: larceny by a servant. Convicted of the charge, he was sentenced to a six-month term, which he likely would have served in the county jail.

One year later, on February 3, 1853, Berrow’s Worcester Journal described Isaac as an “old offender” when he was charged with stealing four gig cushions: two from Samuel Smith and two from William Mansfield Bill. (A gig is a light, two-wheeled cart pulled by a single horse). On the same day he was also charged with uttering (passing) two half-crowns to John Rupert Salt of the King’s Arms of Alcester Lane’s End, [south of Birmingham] knowing them to be false and counterfeit.” After he was arrested he gave the police an alias: Charles Gines. (Spelling was not standardized and this surname was likely pronounced “Jones.”)

The King’s Arms pub (on the left), in 1911. King’s Heath Local History Society

On March 1, 1853, Isaac was convicted of all the charges. Because it was his second offense, he was given a harsh sentence: Seven years transportation. However transportation to the colonies had been mostly phased out by 1853. (Don’t ask me why they were still handing out the sentence if they weren’t actually doing it, but apparently many well-off Englishmen decided it wasn’t really punishment to send convicts to Australia, where they might have a better chance of economic success than they did at home.) Instead he was sent instead to the Wakefield House of Correction, an ancient prison in West Yorkshire.

Isaac Ellery’s prison record from Portland Prison. Ancestry.com

Prison records at the time of his conviction describe Isaac as a single man, 21 years of age, able to read but not write. His health was described as “very good.” His character and conduct were also considered “very good.”

He was incarcerated at Wakefield for just over a year. On April 28, 1854, he was transferred to Portland Prison on the Isle of Portland, off the coast of Dorset in southern England. The prison, which opened in 1848, was built to house convicts sent there to construct the breakwaters of Portland Harbor and its related defenses. (The Brits were concerned about attacks by the French). The work would have been “hard labor.” It may be that Isaac — a young, strong man — volunteered to go in exchange for an early parole date. and his prison record backs this up. After two years at Portland, he was awarded a license by “Her Majesty” (Queen Victoria) to be “at large in the United Kingdom.” For some reason his parole was revoked in May 1858, and he was sent back to Portland Prison, according to UK Prison Commission records.

On February 29, 1860, his sentence expired. Isaac was released from custody.

And then he vanished. His parents and siblings continued to live in the vicinity of where Isaac was born, but he is not with them. His death was not recorded under the name “Isaac Ellery.”

There are questions I can’t answer. For instance, why did he steal gig cushions? He certainly wasn’t wealthy enough to own a gig. He committed his crimes during the dead of winter, and if he was so hard up he needed to steal to survive, wouldn’t it have been better to steal food or a warm coat? Passing coins he knew to be counterfeit also seems like a strange thing for a farm hand to do. Presumably the reason he used an alias was to disguise his identity. It didn’t work, but it let’s us know he was familiar with the concept.

As far as his mug shot is concerned. I believe it was taken around the time he was released from prison. He looks closer to 30 years old than to 21. In 1859 Robert Evan Roberts, the Governor of Bedford Prison, began photographing recidivist prisoners and storing the photos for the purpose of identification in case they reoffended. Isaac was never held at Bedford Prison, but there may have been other prison governors who tried out Roberts’ new idea. Photography of prisoners was instituted nationwide in the U.K. in 1870.

I wish I knew what became of Isaac after he left prison, but photos and records only go so far in telling someone’s story. My guess is that he returned to where his family lived but changed his name. A new identity might have helped him find employment more easily and it would have protected his family from the infamy of having a relative in the area who’d served a long prison sentence.

When I finished my research, I realized that whether or not Isaac’s photo was the first mug shot ever taken doesn’t really matter. It’s a wonderfully evocative image of a poor man who was harshly punished for a crime that wouldn’t even warrant a mention these days.

I thought the reports of what he stole sounded odd, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hard to know what to make of it! Thanks, Liz!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is! You’re welcome, Shayne.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great research & writing! Wow, that’s a long time ago to have so much information. Congrats, you are one excellent sleuth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I take that as a big compliment coming from a sheriff!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a great portrait, and I completely agree that he looks more like 28 than 21. He looks tough, like a man who served time and figured out how to survive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure those qualities were necessary! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person