Pearl Clifton had a serious love of drink, along with a tendency to be reckless, which her taste for booze didn’t help. On the night of February 27, 1897, her world came crashing down when she was arrested after her ill-fated attempt to burn down her house at 250 Normal Avenue in Buffalo, New York.

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t her house. She’d put a down payment on it, bought furniture and moved in, but she still owed most of the purchase price, including a payment that was due the next day. She’d insured the house and furniture to the tune of $5,500. (Close to $200,000 today.)

Pearl and two pals, Maud Gallagher and Josie Lewis, started drinking at “The Straight” saloon early that fateful day. By the time evening rolled around, the girls were three sheets to the wind. They left the bar and headed to Pearl’s house, where the drinking continued. According to Pearl’s later testimony, while they sat around the kitchen table, she and Maud cooked up a plan to burn down the house for the insurance money. If it worked at her house, they would set Maud’s house on fire and collect the insurance payout on that house too. Needless to say, common sense didn’t play a major role in their decision-making.

Depending on whose story you want to believe, either both women (Pearl’s version) or Pearl alone (Maud’s version) went from room to room, lighting the curtains on fire. An alert passerby noticed the fire and called the fire department. The fire was put out before any significant damage occurred. An investigation into how the fire started led to both women being charged with attempted arson.

But here’s the thing that really got people’s attention: Pearl earned her living as a prostitute. At her arraignment, according to The Buffalo Commercial newspaper, “Police court was packed with morbidly curious people.”

The Buffalo papers extensively covered the story of Pearl’s life, the sordid side, anyway. Only 22 years old, she claimed to have been arrested many times in the past. She made it clear, however, that she drew the line at the Badger Game. She’d never do that, she insisted. She was described by the Buffalo Enquirer as being “young in years but older than the hills in crime,” implying that though she looked like an innocent girl, she was really an experienced criminal. The newspaper also described Pearl as “not a beautiful young woman, as reporter’s ravings would have people believe, but exceedingly common-looking.” The irony of insulting Pearl’s appearance while making money using her story to sell newspapers was lost on the newsmen.

Pearl went by several aliases, but her real name was Annie Laura McGinness. She was the last child born to her parents, William and Margaret McGinness, before they left Ireland for America. The family settled in Buffalo, where her father worked as a unskilled laborer. All told there were six girls and three boys in the McGinness clan.

Pearl enjoying the media attention she received and gave many interviews to reporters. She claimed she had left home at the age of 12. To support herself she began to do sex work in Buffalo resorts (brothels). Eventually she plied her trade in other cities as well, including New York City. There she got chummy with a client named Mills Wagner Barse, the scion of a wealthy New York family. His father, Claudius Victorius Boughton Barse, made a fortune in the hardware business in Olean, New York. Mills Barse was handed every advantage in life. He attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. After he graduated, he was given a prestigious job at the bank established by his father, who died in 1885.

Mills Barse, however, was more interested in carousing and partying with prostitutes than in banking. A man named Charles B. Newhoff, who Pearl stated under oath was her stepfather, told reporters that Barse supported Pearl for several years while she tried her luck on the dance hall stage and at running her own brothel. Newhoff claimed that Barse had reneged on a promise to marry Pearl and had withdrawn his financial support. Pearl, he said, then brought a breach of promise suit against Barse. Barse, who was a spendthrift, obtained the money to pay Pearl off by signing his mother’s and sister’s names as sureties for a loan without their knowledge and permission. The bank intervened when it discovered the deception. Possibly in a bid to get back at Barse, Pearl signed her name on the deed to the house “Laura Barse.”

By the time she tried to set the house on fire, Pearl was heavily in debt and desperate. Still, getting drunk and having a witness—Josie Lewis—to the evening’s events was not smart. She ended up pleading guilty to the charge of arson. Maud changed her guilty plea to innocent and went to trial. She too was convicted of arson. Both women were sentenced to two years and six months at Auburn State Penitentiary in Auburn, New York.

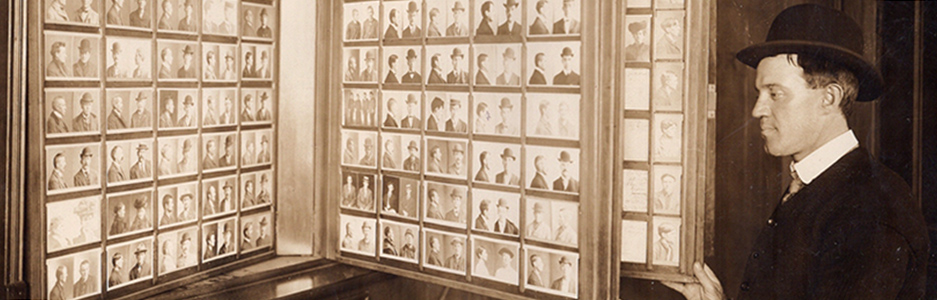

The police in Buffalo thought it was a good idea to share Pearl’s identification card with the police in New York City, just in case she should ever venture that way again. She looks really young and a little bit scared in her mugshot photo; not at all like the hardened “older than the hills in crime” woman the papers made her out to be. I wonder how she managed at Auburn, where prisoners were held in solitary confinement and silence was enforced by guards at all times.

By 1900, according to the census, she’d been released from prison and was back home, living with her parents and siblings in Buffalo and working at a button manufacturing company. It must have been a come down after all the requests for interviews, not to mention the attention and drama of testifying at trial. But it also must have been good to be able to talk without asking for permission.

By the way, there is no evidence that her mother was ever married to anyone besides her father, so Charles B. Newhoff’s role in the Pearl Clifton saga remains a mystery. After that 1900 census, I lost sight of Annie McGinness, alias Pearl Clifton, alias Laura Barse. Here’s her family tree.

Something tells me she didn’t spend the rest of her life making buttons. I hope she was able to kick the drink after she got out of the slammer. She was only about 25 at that point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope so too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pearl looks like a child!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

She sure does!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Shayne, thanks for the story. Enjoyed it. Jim

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad!

LikeLike