Mrs. Catherine O. Neill will have to spend her Christmas in the Tombs Prison, much as she desires to be taken to Connecticut to be tried on the charge of murdering her husband, Joseph Neill, on the night of Dec. 14. Sheriff Rich of Greenwich says that this is due to Gov. Higgins being away from his executive office until after Christmas.

—New York Times, December 23, 1906

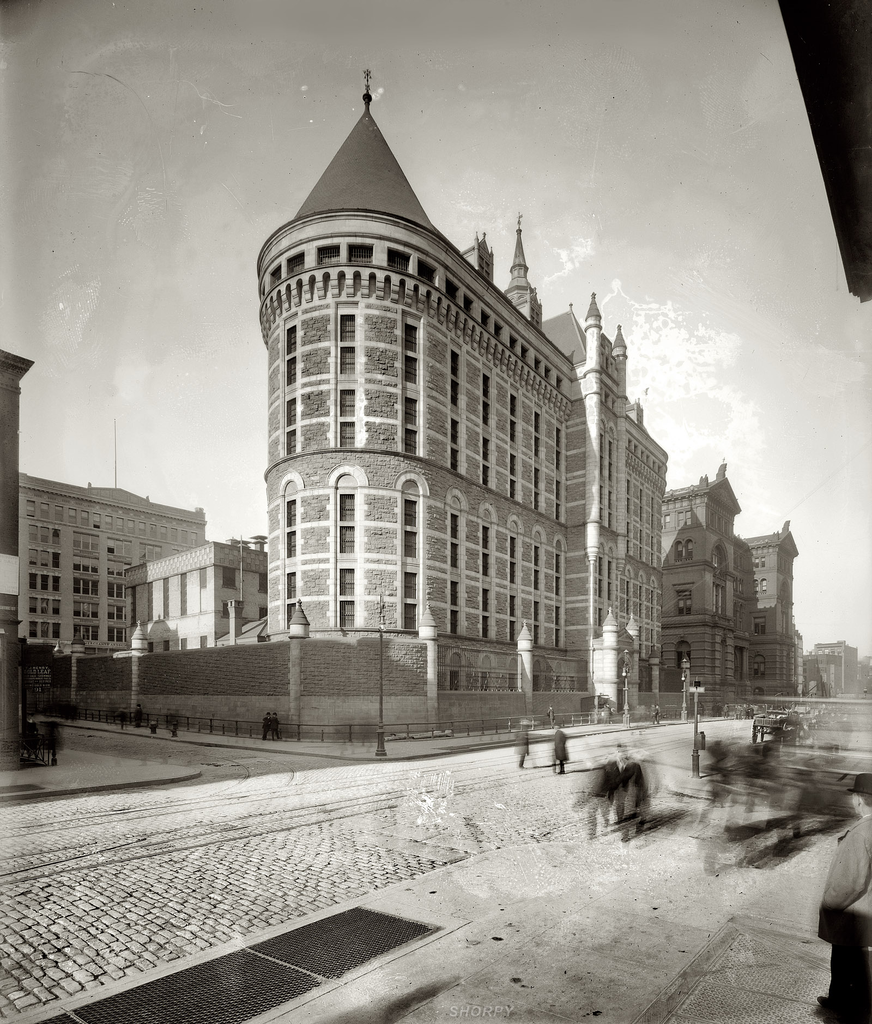

Despite its creepy name, the Tombs Prison had nothing to do with graves, crypts or burials. Located in downtown Manhattan, the Tombs was so-named because the design of the original 1838 prison building was said to have been inspired by an Egyptian tomb. In 1902 that building was torn down and a building resembling a turreted French castle replaced it but “The Tombs” nickname stuck.

The Tombs Prison as it looked when Catherine was lodged there, George Grantham Bail Collection, Library of Congress.

No matter what inspired the architects of the prison in lower Manhattan, Catherine, or “Goldie,” as she was known, was there because she’d been accused of murdering her husband in an especially revolting way: Joseph Neill’s brain had been pierced with some kind of sharp instrument that killed him.

The couple met in New York City’s Tenderloin district in September 1906. At the time Catherine was estranged from her first husband, a policeman named William H. Finley, whom she married when she was just 17. Joseph persuaded Catherine to divorce Finley and marry him. But when their marriage took place, her divorce had not been finalized. Joseph became enraged when he discovered that his wife was a bigamist. He threatened to make a new will and leave his money to another woman.

Their marital problems escalated during a vacation a few months after their marriage. They were staying at the Greenwich Hotel in Connecticut when Joseph got drunk and attacked Catherine. She insisted she was only defending herself and had the bruises to prove it. She said she grabbed her umbrella to ward off the blows and her husband stumbled, falling forward. His face, she said, was accidentally impaled on the pointy end of her parasol. She fled from the hotel and took a train home to New York City. She sought refuge at her mother’s home. The police found her there and arrested her.

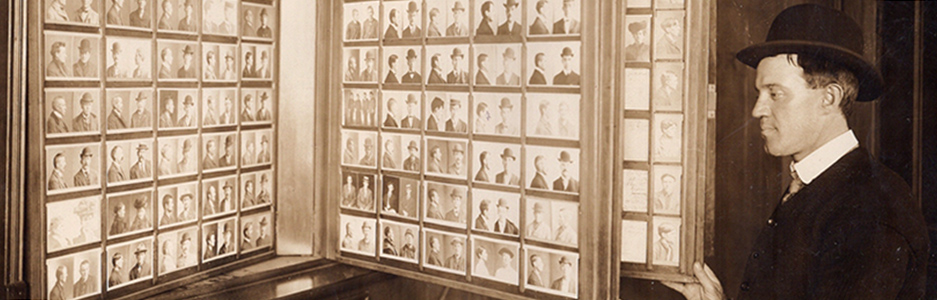

There was no doubt that the burly Joseph had badly beaten his wife. She had a black eye—it’s clearly visible in her mugshot photo. However an autopsy revealed that he’d been drugged before he died. The prosecution maintained that Catherine did the drugging. According to their explanation of events, after her husband became unconscious, Catherine pulled his eyeball aside and inserted a sharp object into his brain through his right eye socket, causing his death. The murder weapon—a pearl-handled nail file—was found in the folds of Catherine’s parasol.

News illustrations of the Connecticut hotel where Joseph Neill died, Catherine ”Goldie” Neill and the possible murder weapon (a nail file), The Indianapolis Star, May 20, 1907.

The press ate up the sordid drama of the couple’s story. They compared Catherine to Evelyn Nesbit, the original “Gibson Girl,” even though Evelyn had never been accused of any wrongdoing. In June 1906, Evelyn’s husband, a psychotically jealous man named Harry Thaw, shot and killed her former lover—the architect Stanford White—in front of a large crowd at Madison Square Garden. The only similarities between the two cases were that Catherine and Evelyn were both pretty young women from the lower rungs of society and both had worked as artist’s models and chorus girls.

Catherine “Goldie” Neill in her artist’s model days, The Spokane Press, Mar. 11, 1907

Harry Thaw, the son of a wealthy family, was tried twice for the murder of White. His second trial ended in a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. After a few years at a cushy asylum, from which he escaped, Harry got a third trial. He was found not guilty and set free.

Unlike Thaw, Catherine had no money for expensive lawyers. She pleaded guilty to manslaughter on May 22, 1907. The judge sentenced her to a minimum of five and a maximum of nine years in the Connecticut State Prison. She applied for a pardon after two and a half years in prison, using the “he fell on my umbrella” explanation of her husband’s death.

Keeping a lovely young woman cooped up in prison didn’t seem right. The prison authorities accepted Catherine’s account of Joseph’s accidental death. She was granted a pardon just before Christmas in 1909.

Catherine returned to New York City under an assumed name to avoid publicity. As a free woman, the first thing she said she intended to do was embrace her seven-year-old child from her first marriage—a child that was blind from birth.

Featured photo: Catherine O. Neill’s mugshot photos, Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, collection of the Library of Congress.

Another very strange case from the archives. I think the fact that her husband was drugged negates the “fell on my umbrella” defense.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s possible he was self-medicating. (So many drugs were available back then for the asking!) Plus I’m not sure I’d trust forensic toxicology in 1906. But knowing she was being abused, I wouldn’t blame her for fighting back. Thanks, Liz!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You could be right. I hadn’t thought of that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Her mug shot image looks so different from the artist’s model one. Did she ever marry again?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree that the photos do look different but, she was looks quite young in the artist model photo. I found nothing about her after she was released from prison. Thanks Eilene!

LikeLiked by 2 people

As always, excellent photos & story. I agree, “he fell on my umbrella,” sounds far-fetched, but being severally abused leads to desperate acts & creativity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your comment, Jim!

LikeLiked by 1 person