Thirty-two-year-old Frieda Trost gave the prison photographer a wide-eyed, stoic stare. Despite not showing any sign of emotion, she had plenty of reason to be afraid. Frieda had just been convicted of murdering her husband, William Trost, and was facing the noose. If her sentence was carried out, she would be the first woman executed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania since Sarah Jane Whiteling was hanged for the murder of her husband and children in 1889.

A baker by trade, Trost hadn’t been a rich man, but he owned property worth about $3200 (approximately $85K in today’s money). He also had a life insurance policy worth several thousand dollars. A week before his marriage he made a will, at Frieda’s request, leaving his estate to “his intended wife Freda Hartman.”

Six days after the wedding bells rang, Trost was dead. Tongues began to wag.

People said that Frieda had run up a lot of debts and had married the middle-aged bachelor not out of love, but for his money. The timing of Trost’s demise, his prenuptial will and the bride’s close friendship with the bartender in her saloon — all of it looked bad for Frieda.

The coroner performed an autopsy on Trost’s body, and 751 mg of arsenic — more than enough to kill an adult — was found in his stomach. His death was ruled a homicide and Frieda was charged with his murder. The bartender, Edmund Guenkel, was charged as her accomplice in the crime.

In case you haven’t guessed, all the main participants in this drama were German-born immigrants to America. Frieda Götz was born in Germany around 1881. She arrived in the United States when she was 18 and settled in Philadelphia. In 1900 she married Frederick Hartman, a German-born baker nine years her senior.

Tragedy dogged the Hartman family. Their first child, a son named Frederick, was born in 1901; He lived less than two months. A daughter — called Frieda, after her mother — came along in 1902; She died when she was five months old. Anna May, born in 1909, was stillborn or died soon after birth. Of the four Hartman children, only Irene Paulina, born in 1904, lived to adulthood.

Frederick Hartman made a will in 1907, leaving his estate to his wife. He died of “congestion of the lungs” in February 1911. Frieda used the money to buy a building on Germantown Avenue, where she and Irene lived on the second floor and she operated a saloon on the first floor.

The bartender at the saloon, Edmund Guenkel, was a married man with a wife and two daughters. Guenkel’s wife claimed he was innocent. She insisted that her husband’s relationship with Frieda was business-only.

After Frieda was charged with murder, Christian Hartman, her first husband’s brother, voiced his opinion that she had also poisoned his brother and their first two children. “He died suddenly and there was a number of suspicious circumstances about his death,” Christian said. He demanded that the bodies be exhumed and examined.

Exhumations are expensive and unpleasant. The authorities indicated they did not suspect Frieda of having anything to do with the deaths of her children, but they announced plans to exhume the body of Frederick Hartman. If his body was autopsied, the press did not report on it and Frieda was not charged with any wrongdoing related to her first husband’s demise. Still, the rumor that she poisoned her family hung over her like a dark cloud.

So what happened in the six days between the wedding and Trost’s death?

After the marriage the newlyweds planned to live in Frieda’s residence above the saloon. A wedding reception was held on the evening of Thursday, August 1, 1912 at the saloon. According to coverage of the trial in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Trost became angry when his new wife showed Guenkel too much attention at the party. He stormed out and went off to stay with friends.

He stayed away until Monday, August 5. That day he called the saloon and spoke to Guenkel. He said he had injured his foot while riding a streetcar and wanted his car brought to him. The bartender told him the car was in the shop for repairs. Guenkel and another employee went to meet Trost and the three men returned to the saloon via streetcar. Trost then went upstairs to bed.

The next day Dr. George Hatzhausser came to the house to examine Trost’s injured foot. Hatzhausser said he found no signs of injuries, but the baker wasn’t well. He said he thought Trost was “under the influence of chloral or opium.” He gave him a prescription and left. Trost died the following evening, August 7, 1912.

Emil Vogel, who ran a nearby drug store, testified that he had sold arsenic to Frieda. Catherine Ehrler, a servant in the Trost home, said she saw Frieda mixing a white powder in a glass at Trost’s bedside.

The prosecutor stated that two weeks before the marriage, Frieda said, “I am going to marry a rich baker; I do not love him, and I would marry him right away if I thought he would die in seven days.” Murderers don’t normally announce their intentions to kill someone. Unfortunately the Inquirer article did not mention who reported this incriminating comment to the prosecutor.

Frieda maintained her innocence throughout the trial. She said she’d bought the arsenic to poison cats. She insisted her new husband had committed suicide by consuming the arsenic. She didn’t behave the way a woman was expected to behave during her trial; She didn’t cry or show emotion of any kind. This worked against her, making her appear callous to onlookers.

The jury reached their verdict in 20 minutes: They found Frieda guilty of first-degree murder. Because she was unemotional and seemed resigned to her fate, the press dubbed her “The Woman Without Tears.” But Frieda was born and raised in Germany, where demonstrations of public emotion were strongly discouraged.

The bartender was found not guilty at his trial in April 1913. He and his wife stayed together until her death in 1944. He died in 1953 in Saint Lucie, Florida.

According to the Evening Public Ledger, Frieda thrived in prison. Described as a “model prisoner,” she worked as a seamstress and kept her cell spotlessly clean. Her sister, Rose Gressel, came to visit regularly. Her daughter only visited once during her first year in prison.

Women prisoners had always been in the minority at Eastern State. In the early 1920s, Prohibition swelled the prison population and authorities decided to move the women to other prisons. In 1923 Frieda was the last female prisoner transferred out of Eastern State. (She missed Al Capone by six years.) She was sent to the Muncy Industrial Home for Women. By 1930 she was held in Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison.

Just before Christmas in 1938, Frieda was paroled. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that she had taken a new name and was looking forward to spending the holidays with her married daughter.

You can’t help but wonder if she did it. The evidence against her was pretty convincing–but also purely circumstantial. I’m glad she got out.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m still wondering!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a strange tale. Like Brad, I have to wonder if Frieda actually committed the murder.

LikeLiked by 2 people

All I can hope, Liz, is that you found the story worth reading, even though the mystery could not be solved!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I did find the story worth reading. It seems that a number of the crime stories you unearth are like this. That there are so many gives one pause.

LikeLiked by 3 people

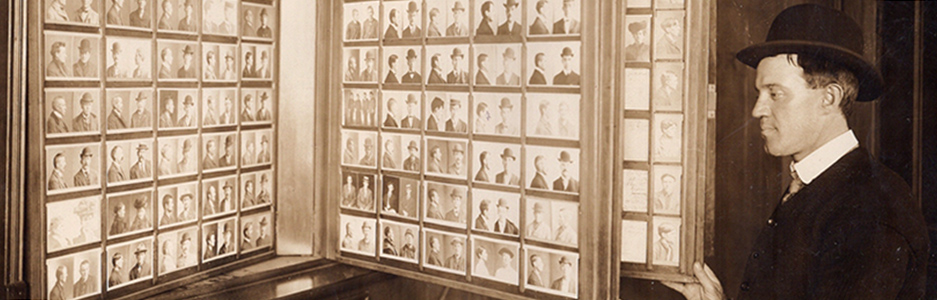

There’s a story behind every photo. You are a master of telling the stories behind your family photos! For some reason I’m drawn to these mugshots and trying to find the stories behind them!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for the compliment, Shayne! You and I are of like mind with wanting to find the stories behind those faces.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it’s likely Trost killed himself, or possibly he was given arsenic by the pharmacist by mistake? The latter is reaching but the idea did pop in my mind. And the witnesses to what Frieda said and did…they might have simply gotten caught up in the press frenzy and lied.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He was reported to feel that the marriage to Frieda had been a mistake. If he was depressed, I believe he could have committed suicide. Lying by witnesses is certainly a possibility!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Poisoning yourself would be a very painful/uncomfortable way to commit suicide, and most poisonings are committed by women, so I wouldn’t be surprised if she had.

LikeLiked by 1 person