A few months ago I bought 15 rare photos from an established Oakland ephemera dealer who sells vintage mugshots. Here’s what he knew about the photos:

“These came in the large collection I purchased of San Francisco police mug shots over twenty years ago. A man in his 90s sold them to the owner of the antique collective I was in and I purchased the collection from him. Apparently he had stored them in his garage after they were tossed out.”

Each photo is a portrait of a woman. They are not mugshots. The photos are RPPCs, an abbreviation for “real photo post card.” RPPCs were not printed by offset press or lithography. An RPPC is an actual photo printed from a negative—that’s why it’s “real.” In the early twentieth century, when interest in photography was booming, companies began offering a service to print a customer’s photo on card stock, with one side being the photo and the back having a postcard imprint. Voila! You had a photo your own photo you could mail to friends and family. RPPCs were sort of the Instagram of the early 20th century.

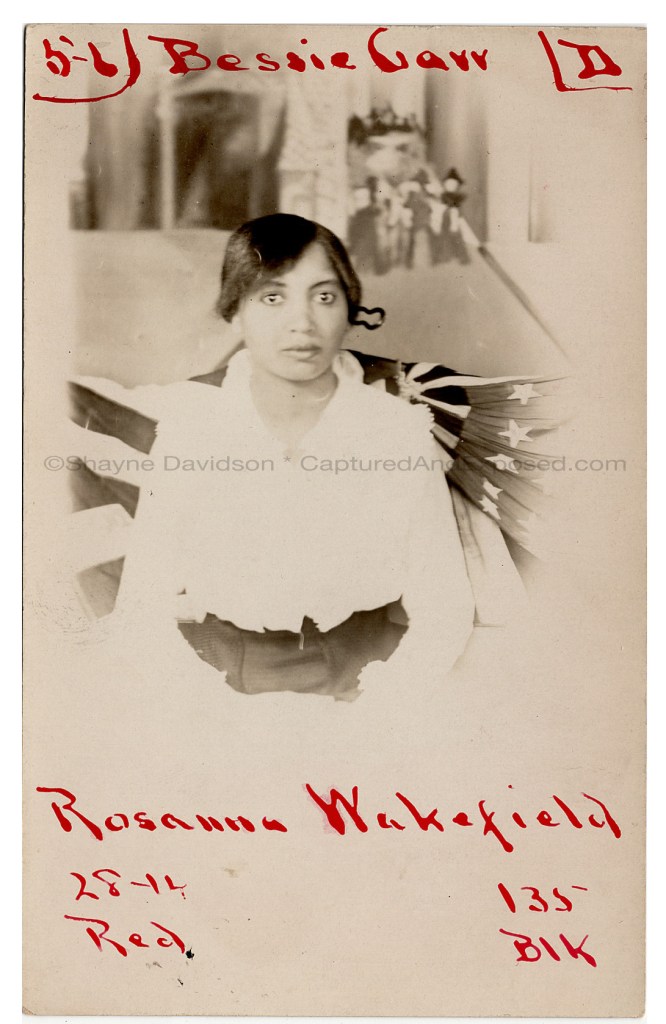

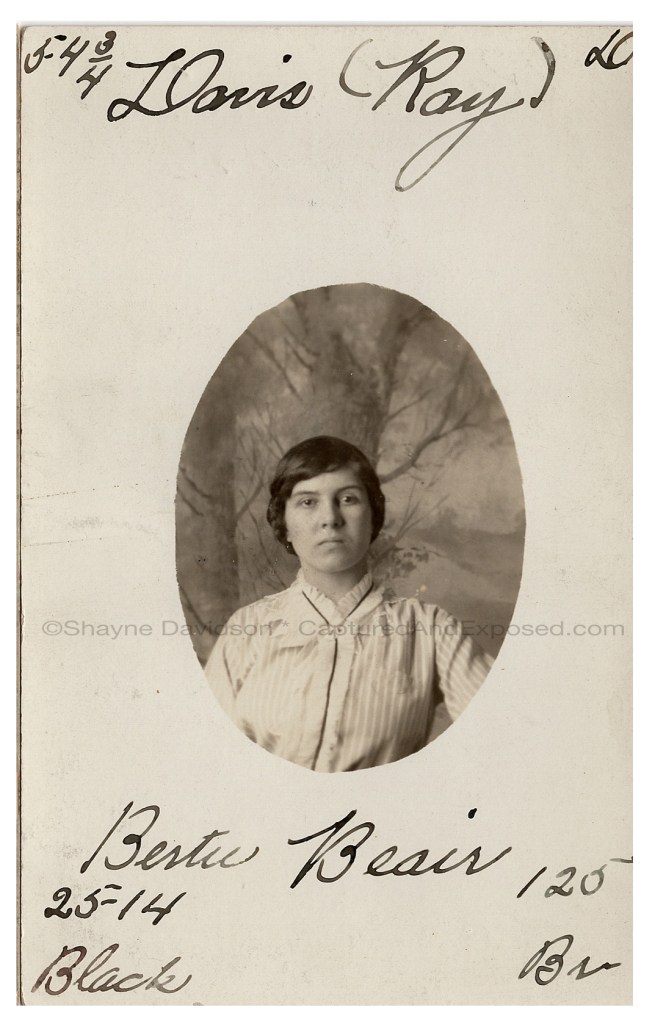

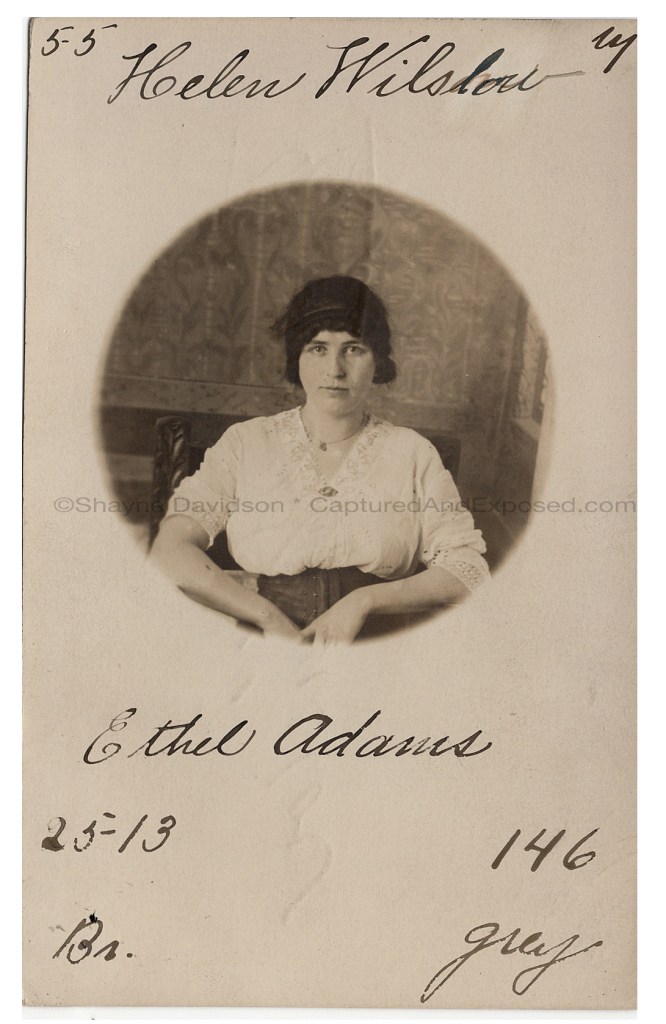

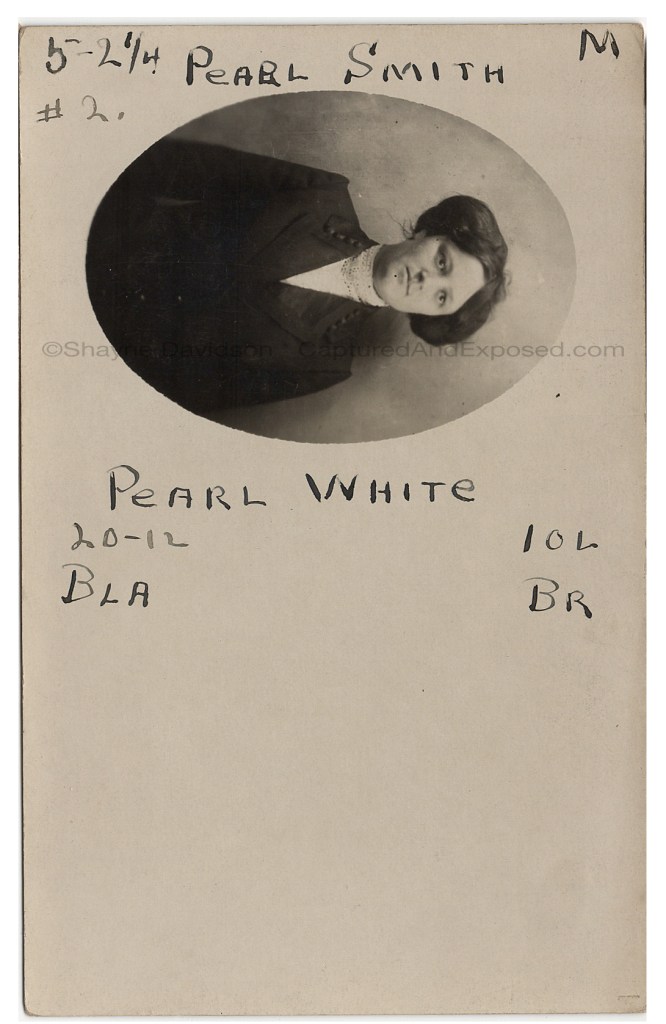

The RPPCs I purchased all have handwritten information on the fronts. In addition to two names, there’s also weight, eye and hair color listed. All but one has what’s likely the woman’s height on the upper left corner. There are also mysterious hyphenated numbers, for example “29-13,” written on the lower front left. I suspect the first number is the woman’s age and the second number is an abbreviation for the year. If I’m right, that means they were made between 1912 and 1914. Most of the cards also have a single letter—B, D, or M—written on the upper right. I don’t know what the letters mean. All but one are signed on the back, in pencil or ink, with one of the two names on the front.

Hoping to find out more about the women in the photos, I searched period newspapers, federal censuses and city directories for both names on each of the cards. For the most part I came up empty, but I did find a few nuggets of information in newspapers.

An article in the SF Examiner titled “Unidentified Hero Saves Life of Girl” described how Rose Curtis, “an attractive 20-year old girl,” fell from the Third Street Bridge into the Mission Creek Channel in October 1913. (The bridge she fell from was replaced in 1933. That bridge still exists and is just south of Oracle Park, home of the SF Giants.) Rose was rescued by the “unidentified hero” and taken to a hospital. Rose told a reporter that she had recently come to San Francisco from Portland and had been unable to find work. She also claimed she had stumbled and the fall was an accident. Could the “hero” who “rescued” her have been a client or pimp who got angry at her and shoved her a little too hard, causing her to fall? We’ll never know because there was no follow up in the newspaper.

An even more harrowing event occurred at the San Francisco Ferry Building. A man named Richard Fleischner threw acid in the face of May Smith, also known as Maggie Sanders, in October 1915. Six months later they were both arrested in Chicago, according to an article published in the SF Examiner on March 29, 1916. Fleischner, who was wanted in San Francisco for pimping and sex trafficking, had “persuaded” Sanders to leave the city after the acid throwing incident. (There was no mention of whether or not she was injured.) He was also wanted on a federal “White Slave” (forced prostitution) charge. The feds planned to bring Sanders back to San Francisco on a “detained witness warrant” to testify in his case. On April 3, 1916, the Chicago Tribune reported that immigration authorities had filed the paperwork necessary to deport Fleischner on the grounds that “he got his citizenship papers through fraud and that he was the keeper of houses of prostitution.” There was nothing about what became Sanders but being attacked by a mobster involved in sex trafficking, then being forced to testify against him must have been a harrowing experience.

Based on my research, the only woman in the group who was ever arrested was Irene Smith, and her arrest occurred four years after her RPPC was made. On December 1, 1917, Irene was charged with conducting a disorderly house (aka brothel) on Natoma Street according to the SF Chronicle. She was held for a Grand Jury hearing. There was no follow up about her case, so likely the charge was dropped. Of course Smith is a common surname and it’s possible the arrested woman was not the same Irene Smith who smiles cheerily in her photo.

Below are the women about whom I was unable to find any information (click to see larger images). One thing they have in common is that they all look unhappy to be photographed.

I also bought a set of 24 index cards (no photos) from the same seller. The index cards were made in the same time frame as the RPPCs, circa 1912-1914. Each card has a detailed record of a female sex worker, with preprinted text, such as “true name” and a space for a hand-written answer. Birth dates and places are also listed, as are the various dates when and addresses where the woman worked. Arrest dates, if any, are listed too. None of the names on the index cards match the names on the RPPCs, but written on one of the cards is: “her card & Picture was here before.” I believe this comment is a reference to the RPPCs.

Sex trafficking of Chinese women and girls occurred during the late nineteenth century in San Francisco. Most of the addresses where the women on the index cards worked are in San Francisco’s Chinatown. However none of the women listed on the index cards is Asian; all 24 women are either white or Black.

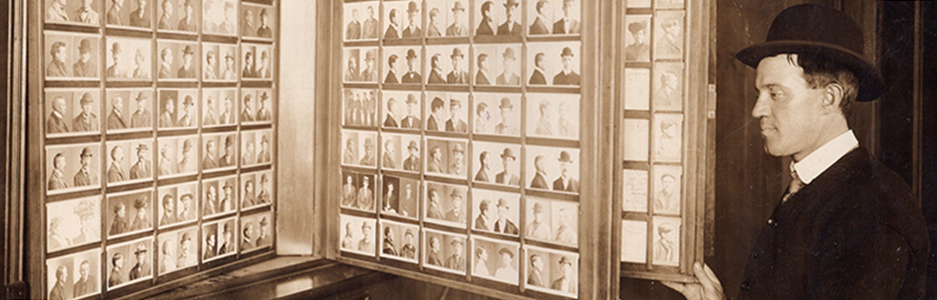

By 1915 prostitution began to be more closely regulated in the United States, including in San Francisco. Here’s a link to an SF Public Library collection of photos—typical mugshots—of arrested individuals who were involved in the sex trade in 1918, 1919 and 1938. None of the women on my RPPCs are in the library’s collection.

Despite having done a lot of research, I still have so many questions about these RPPCs and the women in them. It’s frustrating not to be able to find many answers. It’s clear that the San Francisco police were keeping track of sex workers in the early years of the 20th century. The seemingly unanswerable question is why.

I think you did very well to find as much information as you did!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Liz! I still hope to find out more!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Shayne! I’m confident that you will.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, there probably was money in it for the police. That would be one reason they would keep track of the women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you mean bribes or what?

LikeLike

A very intriguing group of ladies! A big research project like this can be a lot of fun, but the trail sometimes goes cold in the end. It can be hard to know whether to keep digging or to hang up your trowel. It sounds like you’re determined to keep going. I hope you have a breakthrough!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We will see. Thanks, Brad!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is a fascinating collection. Sounds frustrating to research, but seems you’ve put together some pieces.

Sorry I’ve missed your posts – WP stopped showing them in Reader for no reason! I’m sure yours is not the only one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s strange. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I might have mentioned this on one of your other posts, but since it’s so apropos here: this book sheds a lot of light on the lives of San Francisco women who were forced by circumstance to take up prostitution. It was originally published as a series in the San Francisco Bulletin in 1913; the 2016 book version includes letters-to-the-editor from Bulletin readers, reacting to the series. https://a.co/d/cyJaL0S

LikeLike

That’s an interesting book. The story is a sad one.

LikeLike

I figured you had read it! I agree it’s sad. I’m hoping other people who land on this page might give it a look.

LikeLiked by 1 person