No one who follows this blog will be surprised to find that I’m a fan of The Alienist, currently in its second season on TNT. The show, based on the novels by Caleb Carr, vividly brings to life crime in gritty lower Manhattan in the late nineteenth century, complete with dimly lit saloons, dogfights in dark alleys and hungry-looking thugs in derby hats.

And of course there’s murder — the more gruesome the better.

A few characters in The Alienist are based on real people; one of them is Chief Inspector Thomas Byrnes. He’s portrayed by the craggy-faced Ted Levine as a resentful man with an Irish brogue and a vendetta against anyone who disagrees with his hardline approach to fighting crime.

In the first series we meet a disgruntled, newly unemployed Byrnes. Police Commissioner Teddy Roosevelt has booted him from the force in an attempt to clean up corruption (this actually happened). The ex-inspector menacingly hangs around his old station and various local watering holes, trying to stir up trouble.

Two years have passed and Byrnes has started his own detective service when the second series opens. His focus is to protect the reputations and wallets of members of New York high society. New York Journal owner William Randolph Hearst has hired him to dig up dirt in order to besmirch the names of the show’s fictional protagonists: detective Sara Howard, alienist (psychiatrist) Lazlo Kriezler and journalist John Moore.

As a fictional character, Byrnes makes for a great villain. But when a real person is portrayed in a fictional story, things can get a bit confusing. So who was Thomas Byrnes?

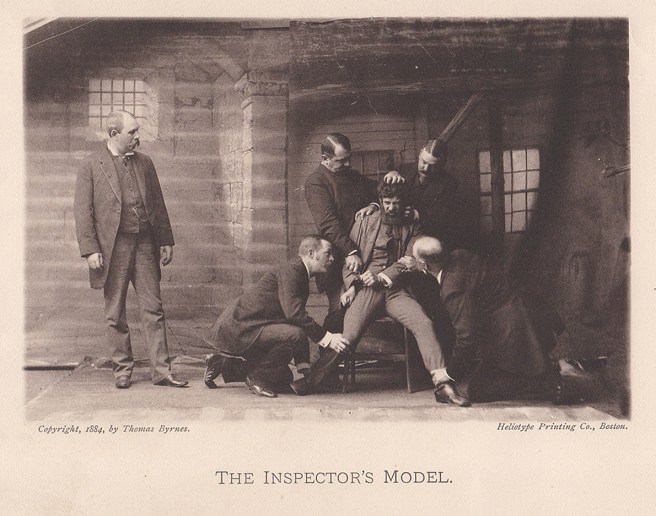

Nicknamed the “Big Policeman,” though he was only 5’11” tall, the name was more a reflection of his policing style than his height. Byrnes had a well-deserved reputation for brutality when it came to the treatment of criminal suspects, which sounds sadly familiar to us today. Journalist and photographer Jacob Riis, who knew Byrnes well, described his interrogation style:

Perhaps he was a tyrant because he was set over crooks, and crooks are cowards in the presence of authority. His famous “third degree” was chiefly what he no doubt considered a little wholesome “slugging.” He would beat a thief into telling him what he wanted to know. Thieves have no rights a policeman thinks himself bound to respect.

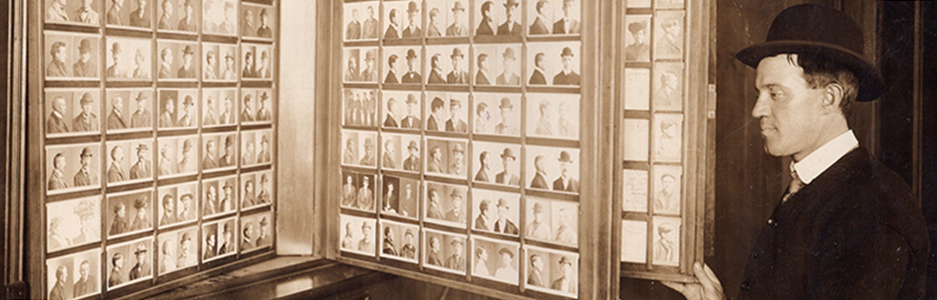

But Byrnes wasn’t just a brute with an iron fist. He did some good things, such as promoting the use of photography to identify criminal suspects. The rogues’ gallery existed long before he became an officer, but he reinvigorated the idea and encouraged it with his 1886 book Professional Criminals of America. A second edition came out in 1895, shortly before he resigned from the police force.

Based on his passport application, filed in October 1895, he was born on June 15, 1842 in Wicklow, Ireland, south of Dublin. Exactly when he immigrated to America is uncertain, but according to his obituary in the New York Tribune, he arrived in New York as a child. The name “Thomas Byrnes” (or Burns) is extremely common, so identifying him on census or immigration records is challenging and I was unable to find him prior to the 1880 census. By then he had married Ophelia Jennings. He and his wife lived on West Ninth Street in Greenwich Village with their five young daughters.

City directories tell us he began his career with the NYPD by 1867. Byrnes moved up the ranks quickly, and in 1870 he made captain. In 1874 the police department awarded him a gold shield for selling more than 7,000 tickets to a benefit show for the poor of the city. (It’s likely he engaged in more than a little strong-arming to sell that many tickets.) Bigwigs, including politician Thurlow Weed, attended the ceremony honoring Captain Byrnes.

After he located the gang responsible for the robbery of over $3,000,000 from the Manhattan Savings Bank, he was put in charge of the Detective Bureau. It was around this time events occurred that later came back to haunt Byrnes. He established a “dead line” at Fulton Street and promised to arrest any crook that crossed it. The Wall Street bankers and investors loved this tactic and were extremely grateful for the protection. They showed their gratitude by providing him with insider information about stocks and real estate.

By the time Roosevelt forced him to resign in 1895, Byrnes was a wealthy man, thanks to his Wall Street buddies. In 1894 he admitted to the Lexow Committee that he’d made $350,000 based on the advice of Jay Gould and others, but he was probably underestimating his fortune. When he died in 1910 (of stomach cancer) his estate was valued at $1,000,000 (worth close to $28 million today). It may have actually been worth much more, because he transferred some of his Manhattan real estate holdings into his wife’s name before he died.

In season two, episode six (“Memento Mori”) of The Alienist: Angel of Darkness, Byrnes takes a witness to the detective office and shows her a book of rogues’ gallery photos in the hope that she can identify the suspect (no spoilers here). He slams the huge book down in front of her and orders her to look at it. As she leafs through the pages we get a quick glimpse of the photos. At least one is a photo of a real criminal: a pickpocket, shoplifter and “handbag operator” named Ellen Clegg. The filmmakers get high marks for accuracy in their research.

If you’re interested in reading about another woman Inspector Byrnes worked hard catch, check out my biography of Sophie Lyons.

After reading your post, I’ll have to check out “The Alieniest.” Byrnes would appear to give new meaning to the term “dirty cop”!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The show (and the books it’s based on) are not for the faint of heart! I think Byrnes might have been the original dirty cop. Thanks, Liz.

LikeLike

It always bothers me when the people who are supposed to stop the bad guys ARE bad guys themselves. Ugh. Excellent post. I look forward to reading your book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree! I hope you enjoy the book, Eilene!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoy you research & writing. But I am disappointed on how cops got their gold badges. Selling benefit tickets!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well it was New York City in the Tammany Hall years! Thanks, Jim!

LikeLike

I need to check out this show! And your book is on its way to me now. I’m very excited to dig in!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! The show is fun, though gory at times. I hope you enjoy the book. I continue to enjoy your blog!

LikeLike