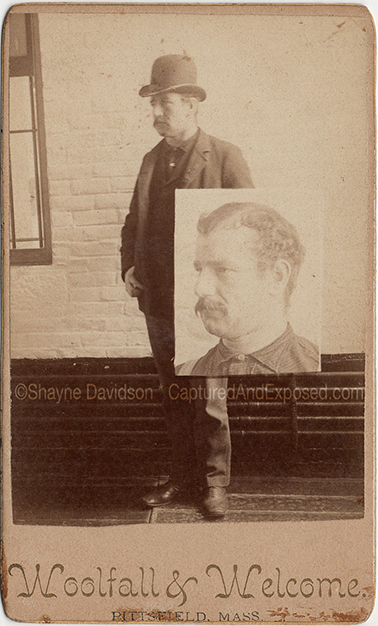

I purchased this photo because I’d never seen another one like it. It was made in 1892 at the Woolfall & Welcome photography studio in Pittsfield, a city near the western edge of Massachusetts.

For those of you who’ve grown up in the era of electronic images, the photo was not easy create. To start, the photographer had to expose two glass plate negatives—one was of the man standing and the other was a close up of his head. After developing the glass plates, the photographer laid the standing negative on the photo paper, masked out the rectangular area and exposed the paper to light. Next the mask was removed from the rectangle and the standing man part of the image was masked out. The negative of the close up was placed on the rectangular area and exposed. All that fiddling around with easily-breakable glass negatives and masks had to be done in the dark so the photo paper wasn’t exposed to light. It’s also possible the two negatives (standing and close up) were printed separately and then pieced together, with the composite photo being rephotographed and printed. Either way, it was a lot of work, which is likely why very few photos like this were made.

This is a rogues’ gallery photograph—aka a mugshot. It’s a CDV, or carte de visite, a playing card size photo that was popular in the nineteenth century. In non-police settings, CDVs were often used as calling cards left at someone’s home or office. But this one was made so the police could identify the man in the future, should he be arrested again. The cash to pay for it was coming from the public’s purse, and at this point, it wasn’t all that clear to the public that taking photos of arrested people was the best use of limited police funds. After all, many of the working public had not yet had their own photo made, so why should they pay for crooks to have theirs done? Or so the thinking went.

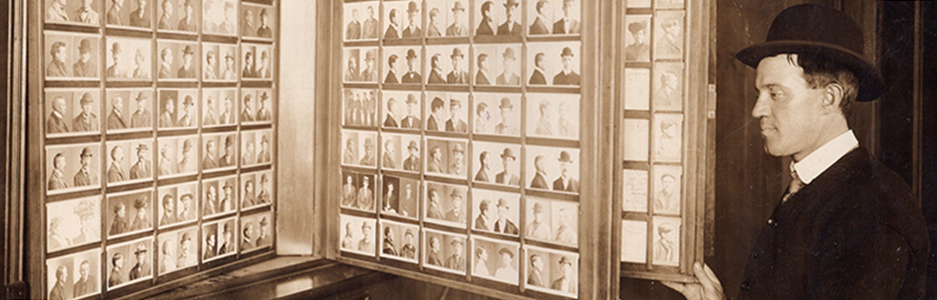

Police photography was rapidly evolving in the nineteenth century. For purposes of identification, the close up is better than the standing portrait. Although it’s the size of a postage stamp, it provides a fairly clear, three quarter view of the arrested man’s face and head. While in the standing photo he looks more generic, resembling much of the middle-aged laboring white male population of the United States in the 1890s: derby hat—check; droopy mustache—yes; short hair, jacket and average build—all present and accounted for.

I wish I could give you the lowdown on why the man in the photos, identified as “James Harnam,” was arrested and what happened to him, but I can’t. Despite trying my best to research him, I’ve come up empty. According to the information written on the verso, James was arrested for breaking and entering on August 27, 1892. He was a 28 year old white male, 5’9” tall, with a florid complexion, dark hair and grey eyes. At the time the photos were made, he was being held in the Pittsfield Jail, awaiting trial.

In the standing photo, I’m not sure if we’re looking at the jail or the photographer’s studio. I’d guess it’s the jail, but don’t quote me on it. At this point in time, most police stations did not have their own camera. An arrested individual would be taken to a nearby photo studio to be photographed. Wouldn’t that have been fun for a paying client, to have a handcuffed person seated nearby while waiting to be called in to have their picture made? At any rate, it would have been a fun story to tell your family later.

Stamped near the bottom on the back of the CDV is the following info:

M. H. Pease. STATE POLICE. LEE MASS

Moses H. Pease, per the 1860 and 1870 federal censuses, was born in Connecticut in 1835. He worked as a deputy sheriff in Lee, Massachusetts, about ten miles south of Pittsfield. In 1880, according to the census, he was employed as a judge. He had also been a member of the “Detective Department” in Lee. Pease died on March 4, 1901 in Lee, according to state death records.

What an interesting mug shot! I’ve never seen anything like it. I think you’re right about its limited usefulness for identifying the miscreant in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be fair, we don’t really know if he was a miscreant! Thanks for commenting, Liz!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point! You’re welcome, Shayne!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very cool!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this image, so unusual! I think you’re right and the jail building is the backdrop. Might his surname be Farnam? I noticed under complexion it reads Florid (having a red or flushed complexion, which I love having this descriptor as it makes imagining him in color so much more interesting), and the F looks just like the first letter in the surname.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great suggestion, but sadly I checked it out and again came up with nothing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic! This blog post has it all. Criminal. Detective. Photographer. Judge. History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jim!

LikeLike

Yes, looking at the F in Florid makes it clear the name written is Farnam (could be Farnham). I take it you looked for news reports around the arrest date?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did! Found nothing but it could be that it was reported in a paper that newspapers.com hasn’t scanned.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot of states have their own digital newspaper sites. Free! Often find things on them not available elsewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! But Massachusetts doesn’t (last time I checked).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually your comment prodded me to double check and there are historic newspapers available through the Boston Public Library! https://guides.bpl.org/newspapers/massachusetts-newspapers-online

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome! Good luck.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another tactic I use for newspapers (also free) is to go to Chronicling America and go to their database of historic newspapers. Search for the state, county, or town you want and see what newspapers exist. Click on “See which libraries have this title.” It gives you the libraries that have it (usually on film) and also the dates covered by each library’s holdings. As long as your search is narrow enough, a librarian will look it up for you. I did that recently for a cousin’s obit from 1872. I saw that the Dayton (Ohio) Metro Library had the paper I needed. Called them and had a digital copy of the obit within two hours. No charge!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great suggestion!

LikeLike