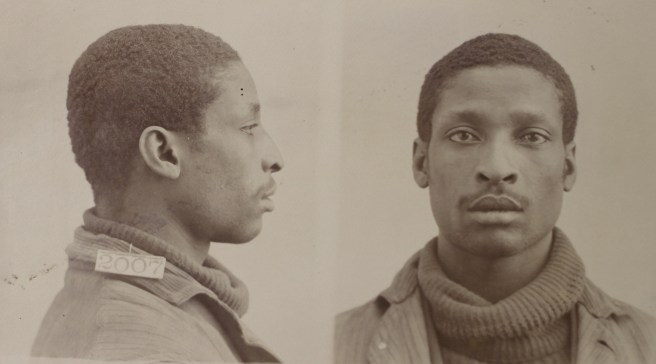

Born in Texas on July 14, 1876, 100 years and ten days after the United States, Nathan Bridgeforth became prisoner #2007 at Leavenworth on February 26, 1900. Seven weeks earlier, he pleaded guilty to forgery in the Northern District Court of Muskogee, Indian Territory. The details of the crime that sent him to Leavenworth have not survived, but it’s a federal lock-up, so it involved falsification of a government document. For this he was handed a ten-year sentence—one of the longest given to anyone who hadn’t committed a violent crime like murder.

Nathan was familiar with prison life, having served time in 1896 at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville—the “Walls Unit” as it was called—for theft of cattle. But then he’d only been incarcerated a few months before being released and granted a full pardon.

When he wasn’t working at Leavenworth, Nathan spent his time corresponding with his many friends and relatives, along with several of his attorneys. He also liked to read and had subscriptions to Cosmopolitan magazine and The Kansas City Star newspaper.

Nathan was regularly written up by the guards for various infractions, including talking, joking around with other prisoners, sharing books and “writing to a lady unknown to the warden.” He wasn’t one to get into fights, however taking orders from the guards didn’t sit well and he was often uncooperative. He paid dearly for it, spending many days in solitary confinement and losing much of the “good time” that would have allowed him to be paroled early.

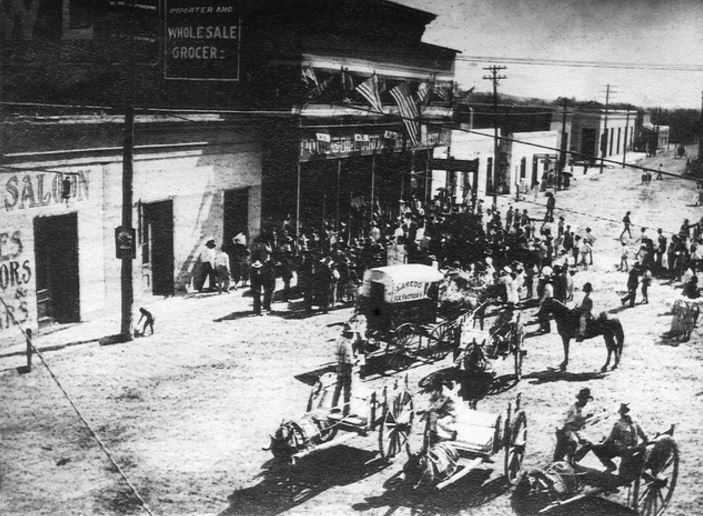

Nathan’s mother, Harriet Phillips, was born a slave in Louisiana. She married David Bridgeforth in Nueces, Texas in 1880. David was born into slavery in Maury County, Tennessee in 1847. In 1870 he enlisted in the 24th Infantry (Buffalo Soldiers) and worked his way up to the rank of sergeant before being honorably discharged in 1875. It’s not certain if Harriet’s sons, William, born 1875, and Nathan were David’s children, but eventually the boys went by the Bridgeforth surname.

During the 1880s David purchased land in Texas. According to his prison intake forms, Nathan was employed as a stockman and cowboy before he was sent to Leavenworth, and he may have worked at a ranch on David’s land.

Harriet wrote to Nathan often while he was at Leavenworth. Or more precisely, she found someone to write for her since when she’d been enslaved, she hadn’t been allowed to learn to read or write. In September 1906 Nathan received one particularly disturbing letter from her:

Laredo Tex

Sept 14 – 06

My Dear Son,

I wrote a letter several days ago, but write again this noon to tell you that your Aunty [Mary] left me on the last Wednesday, and I don’t know where she went and she would not tell me. She has seemed very much displeased now for some times, everything I would do was wrong, & the more I would do, the worse it would be till at last she left. I tell you this for you know this leaves me entirely alone, and if I cannot get someone to stay at my house, why I cannot go out any place to work. She went off alone & I think she has gone to Corpus with a family she used to work for. I don’t write this to worry you but just to let you know how things are here at home. I wrote to your father yesterday & told him that if I had to stay home from this on that he would have to give me a certain amount every month to live on. Have not heard from your brother in some time, it certainly seems as if I have a hard time of it. Mary was so cross & talked so ugly to me that it is almost a relief that she is gone. She may write to you, but don’t say anything to her about my having told you of it. If I have to live this way, I am tempted to sell my home & then we all will be a drift, I have stood about as much as I can. I know you will think this is a blue letter but I have to talk to someone. Be a good boy for you are my only hopes and I pray I will not be disappointed for it will kill me if I am. If you do not get a letter from me often don’t think I am sick for it is a long ways to come to get someone to write you. Don’t worry will write as often as I can. With best love and wishes that you will soon be home. I am, your mother

Harriet

Nathan wrote to the warden, acknowledging that he’d lost 116 days of good time due to various infractions. Nonetheless he asked to be paroled so he could return home and help his mother:

I had a talk with you in early part of the summer in regards this lost time and you said if I behaved myself from that time on you would see what you could do for me. I think that the chaplain will tell you that I am a changed man, that I attend services, bible school and read my bible regularly…You have it in your power Warden to do an old Mother a favor for which both she and her boy on whom she is now dependent, will be ever grateful.

Respectfully,

Nathan Bridgeforth

The warden refused his request, citing concerns about his ongoing unruly behavior.

Finally, after seven years in prison, he was paroled on February 23, 1907.

David Bridgeforth died in June of 1909. Later that year, Nathan was charged with unlawfully carrying arms in Laredo District Court. His “Aunty” Mary Smith had returned to live with Harriet by 1910. By then Nathan no longer lived with his mother.

By 1912 Nathan had moved to Kansas City, where he was charged with shooting at two railroad policemen. Sentenced to one to ten years in state prison, he ended up spending only five months in jail. After he got out he sued the two policemen for having him arrested without cause. His suit demanded $1000 compensation for the rheumatism and lung problems he had developed in jail and another $1800 for deprivation of time with family and friends.

Nathan found a job as a laborer for the Kansas City Light & Power Company. He married a widow, Juanita Page Chapman, and they had two sons together: David, born in 1919, and Sherman, born in 1921.

The family moved to Utah, where Nathan found work shoveling coke at the Sunnyside coal mine. It was hot, back-breaking labor—a challenging job for anyone but especially hard for man in his mid-40s. The mine supplied fuel for the railroads, but it was a dying industry. Before long the mine would close permanently.

In December 1929, Nathan was arrested in Laredo for selling liquor (prohibition was still in effect). He spent the next ten months at the Walls Unit. His marriage did not survive his imprisonment. Juanita moved back to Kansas City and found work as a live-in cook for a family. She died, aged 44, of heart disease on February 22, 1932.

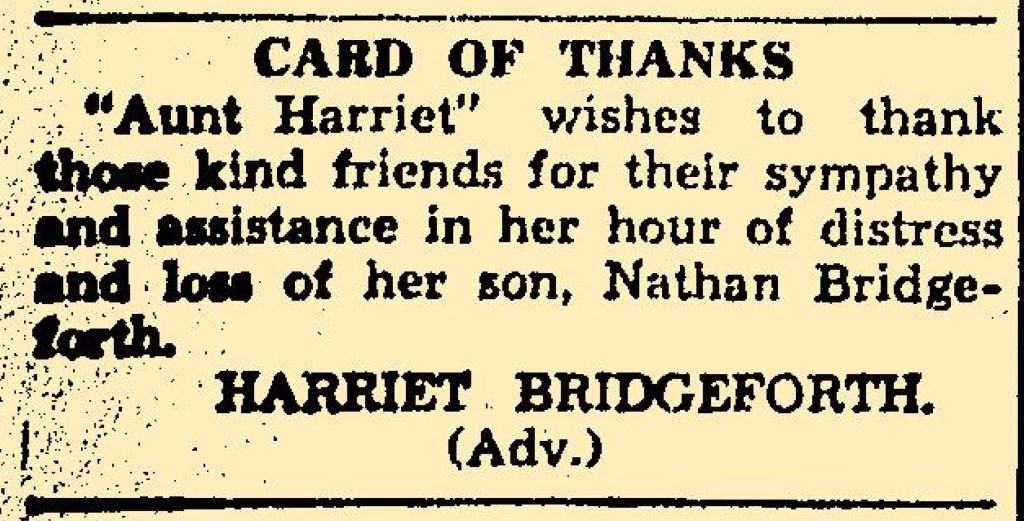

Harriet worked as a midwife and continued to reside in the small house on Chacon Street where she had lived for decades. She married a man named John Battles, but it didn’t work out and they divorced. In January 1940 she died of influenza. The claim on her death certificate was that she was 106, but it’s more likely that she was in her late 80s. (Census enumerators often did a poor job of record keeping of African Americans. Few birth records were kept for slaves and the birth years recorded for Harriet on federal censuses ranged from 1852 to 1875.) Harriet had survived many hardships, including being bought and sold several times when she was a young girl and losing half of her ranch land to an unscrupulous buyer. A couple of years before she died, oil was discovered on land she owned near Corpus Christi. The minerals provided her with a small monthly income.

But Nathan didn’t live to see any of this, because he died on November 20, 1930. And there is a deep mystery surrounding his death. According to his Mexican death record, he died of “asfixia por sumersión” (suffocation from downing). But a newspaper report, published a few days after his death, related an entirely different story.

The article stated that a young Mexican girl left a note at the home of his ex-stepfather, John Battles, the day after Nathan was last seen. The note read:

The body of Nathan Bridgeforth (negro, 54) is in the Rio Grande and it is your duty to get the body of the drowned man out and have it buried.

The note was signed “Lencha.” (Possibly a nickname for “Florencia,” but Lencha could also be a surname.)

Battles contacted the police. They believed the note was probably a hoax, but they started an investigation. Unable to locate the girl, they did, however, discover that the note was no hoax.

Nathan’s partially decomposed body, naked except for some rings on his fingers, had washed up on the banks of the Rio Grande River in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. But his cause of death was not drowning. The Laredo Times reported that there was a bullet hole in the back of his head.

The news article speculated that Nathan might have gone to Nuevo Laredo carrying money for purchases and someone lured him to the river to rob him. Presumably to cover up the robbery, the robber shot him and threw his body into the river.

I guess it might have happened that way. But then again, he had been convicted of selling illegal liquor the previous year. Could it be that he got on the wrong side of some bootleggers and they decided to extract revenge? Were the Mexican authorities bribed to report his death as a drowning rather than a homicide to avoid an investigation? Was the note sent as a warning? Why was he naked? And who was “Lencha”?

The newspaper did not publish a follow-up article. So officially, Nathan drowned. He was buried in Nuevo Laredo.

This is quite a mystery!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it is. Sadly, I’m pretty sure there will never be a solution to the mystery. Thanks, Liz!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Shayne! I had the sense from reading the post that chances are the mystery will never be solved.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great research! Is this family connected to your Civil War portraits?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Brad! No the Bridgeforth family isn’t related to my USCT portraits. A few years ago I did research into people sent to Leavenworth Penitentiary during the prison’s first decade, and that’s how I discovered Nathan’s mugshot. It’s taken me until now to research his life. When I found his Mexican death record (which I asked a Mexican friend translate), I suspected he committed suicide. But then I found the articles about his murder in the Laredo Times. That particular newspaper had not been scanned on the newspaper site (newspapers.com) I use, but it was available on different site.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Many thanks for this excellent review of my book, Alice! I’ll be posting a link in my blog to it!

LikeLiked by 1 person