The smell must have been horrendous when the police finally entered the apartment, given how long the old man’s body had been lying there. It was murder — there was no question about that. He’d been shot with a single bullet to the back of the head. Robbery was thought to be the motive because his pockets had been slit open. But $1,960 in cash and some gold certificates were found in a trunk near the body.

The victim was a wealthy real estate dealer named Ferdinand Hochbrunn. When his body was finally found on December 22, 1921, he’d been dead about two months.

Hochbrunn, a 72-year-old confirmed bachelor, emigrated from Berlin in 1872. He settled in Seattle. The city grew by leaps and bounds in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Hochbrunn made a fortune in real estate in his new hometown. He was ruthless and sometimes deceitful in his business dealings. One of his clients, Olive Stearns, sued him for cheating her out of part of the proceeds of a land sale. The case went all the way to the Washington Supreme Court, where Olive won a judgment of $14,759.

The police were very anxious to speak with the dead man’s “ward,” a young woman named Clara Elizabeth Skarin. She was the daughter of Hochbrunn’s housekeeper, a Swedish-born widow named Emma Ekstrand Skarin. Emma had died suddenly in 1918. After her mother’s death Clara moved to Michigan. But she had returned to Seattle and her mother’s old employer had taken her under his wing. Hochbrunn hired her to work as his secretary and gave her a bedroom in his apartment. Recently she moved out of the apartment into the home of a married cousin.

A neighbor who lived in the apartment below told the police she heard someone walking around the Hochbrunn apartment in late November. The witness said she’d assumed it was Clara. It would have been impossible for Clara not to have noticed the body—it was lying on the floor of an alcove off her bedroom. Other tenants in the building said they’d seen Clara come and go during the months of October and November.

The last time anyone had seen Clara was in late November when she’d had Thanksgiving dinner with her aunt, Marie Datesman, and Marie’s family. At that time she told the Datesmans she intended to meet Hochbrunn in Portland, Oregon.

The Seattle police asked Mrs. Datesman for a photo of Clara. She gave them a snapshot, but it was of poor quality and was useless for identification purposes. She told them it was the only one she had.

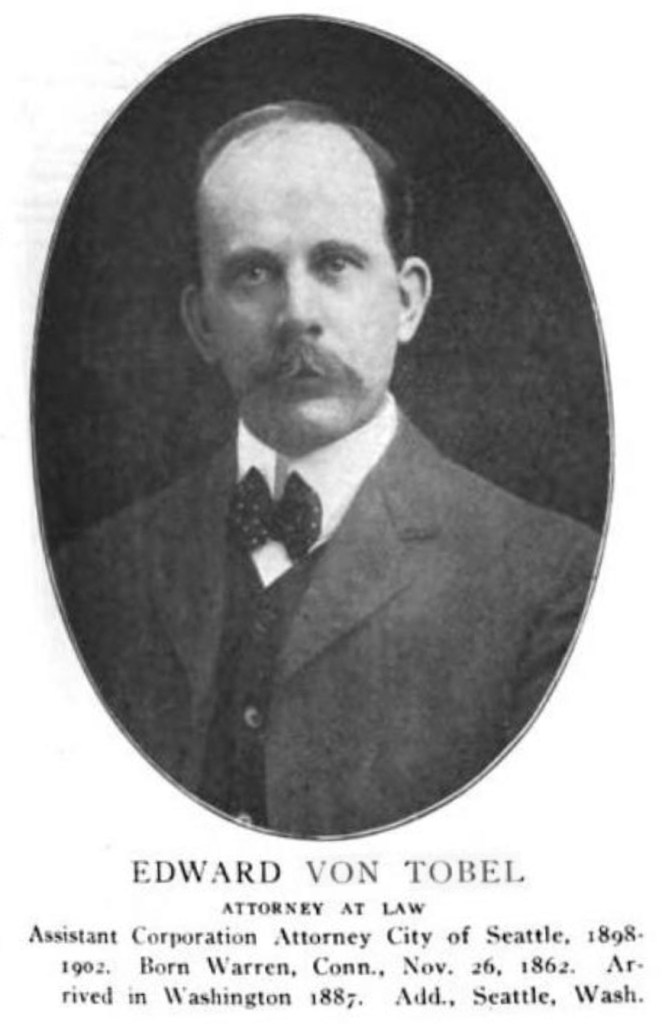

A series of letters and telegrams signed “Ferdinand Hochbrunn” were sent in October and November to Hochbrunn’s attorney, Edward Von Tobel. The messages asked that rents from Hochbrunn’s Seattle properties to be collected and forwarded to him in at addresses in Portland, Oakland and San Bernardino. The messages contained detailed news about his daily life. Von Tobel said he collected the rents and sent the money as instructed.

The police came up with two theories of Hochbrunn’s murder.

The first was that someone killed Hochbrunn and then posed as him, telling Clara by letter or telegram that he’d gone to Portland on business. Clara didn’t know until late November, when she visited the apartment and found the body, that he was dead. Shocked by the discovery, she fled and was wandering around somewhere in a distraught state. The police believed it was even possible that she’d killed herself and her body had not yet been discovered.

The second theory, which soon became the working theory, was that Clara killed her benefactor and stole his money. The police weren’t sure if she’d written the letters and telegrams sent to Von Tobel or if she’d had an accomplice.

The search for Clara expanded to the entire West Coast. In January they missed her by a hair after she made a hasty exit from a hotel in California.

Finally the long hunt ended on September 3, 1922, when an acquaintance from Seattle happened to see her in Oakland and alerted the police. She was quickly arrested.

In Oakland she had been going by the alias “Betty Parrish.”

She admitted that she had shot and killed Hochbrunn, but refused to say any more. She was charged with first-degree murder.

Clara puzzled the authorities. She seemed unfazed about being in jail and wasn’t overly concerned about the charges she faced. She laughed and joked with officers and the newspapermen who visited her at the Oakland Jail, but she refused to talk about the crimes she was accused of committing. A reporter for the Oakland Tribune described her as having a “Mona Lisa Smile.”

She claimed she was able to transport herself, using mental powers, to wherever she wanted to go. She explained her special powers to a reporter:

“Lying here [in jail] at night, I can close my eyes and go wherever I care to. I wander the hills at night. Everything is very real and I don’t feel that I am here at all. I have done that all my life. Sometimes when I have looked forward to a ball I have visualized my being there, and my dancing so realistically that my feet actually ached.”

Her biggest complaint about the jail was that someone had torn some pages out of the Jack London novel she was reading. She praised the Oakland Police Department as “wonderful,” while simultaneously insisting that Oakland was one of the best places in the United States in which to hide.

The police were convinced Clara hadn’t worked alone. They searched for a male accomplice who had used the alias “Phoenix Markham.” Clara refused to say anything about Markham. The police located a telegram she’d sent two days after the murder to a friend named Raymond Herron who worked as a telegraph operator in Kalamazoo, Michigan. The telegram seemed to be written in code. It read:

“Mark here. Everything practically settled. No more saving a half cake of chocolate for tomorrow’s lunch. This is the first of my very own money to spend. May I send Jigadere some of Ollie’s clothes? Buy Maxine a new top and yourself a drink. Am going to order a car here for drive away in spring. Know agent here and want him to get commission. Wire me immediately. Love. BETTY.”

Herron, a 27-year-old Kalamazoo man, married a local girl three weeks after Clara was arrested for Hochbrunn’s murder. The couple’s first child was born a month later. He wasn’t related to anyone named “Jigadere,” “Ollie,” or “Maxine.” Based on the lack of evidence against him, the police decided Herron wasn’t involved in the murder or the cover-up.

The wording of the telegram implied that Clara was Markham. But she was also Betty. Was she suffering from dissociative identity disorder? If so, no one figured that out. The police never located Phoenix Markham and eventually the hunt for an accomplice was abandoned. Clara alone stood trial for the murder.

Previously Clara had been involved in another tragedy that ended in the deaths of two women, one of whom was her mother. The jealous wife of a friend of Clara’s visited the Seattle apartment she shared with her mother in August 1918. The woman, Cleo Winborn, confronted Clara with a loaded gun and demanded an explanation of her relationship with her husband, Robert. Not satisfied with Clara’s answer, Cleo shot at Clara. The bullet hit her in the leg, wounding her slightly. Clara’s mother heard the commotion and ran into the room. Cleo then turned the gun on Mrs. Skarin, killing her with a single shot. Finally she turned the gun on herself, committing suicide.

The person who provided the specifics of what happened that day was the only survivor: Clara Skarin. No one questioned her version of events.

After she recovered from her leg wound, 24 year-old Clara moved with 50-year-old Robert Winborn to his native state of Michigan. By then Winborn, an African-American man who had worked as a barber, was suffering from epilepsy. He was treated at the University Hospital in Ann Arbor, and then transferred to the Kalamazoo State Hospital, a mental asylum. He died of epilepsy at the asylum on September 4, 1919. According to Clara, she and Robert were married while Winborn was on his deathbed. A year or so after his death she moved back to Seattle.

Clara’s trial for the murder of Ferdinand Hochbrunn began in January 1923. She testified that Ferdinand had molested her from the age of 14, when her mother began to work as his housekeeper. She claimed he’d again made “improper overtures” towards her in the weeks leading up to the shooting. This was why, she explained, she had moved out of his apartment. For protection she’d purchased a .32-caliber revolver.

With both her mother and Hochbrunn dead, there were no witnesses to the alleged sexual abuse except for Clara.

The day of the shooting Clara said she’d gone to the apartment to get some clothing she’d left there. Hochbrunn made unwelcome sexual advances, so she pulled out her gun. They grappled over the weapon and it went off, but no one was hit. Then he forced her against a wall. There was a struggle. Clara claimed it ended when she somehow managed to rest the muzzle of the gun on the back of his head and pull trigger with her thumb. He fell to the floor and died about 15 minutes later.

As Hochbrunn lay dying, Clara said she spent several minutes gazing in a mirror. Then she left the apartment and locked the door. She headed to the office of Edward Von Tobel and told him what had happened. She said that she and Von Tobel returned to the apartment and removed $30,000 worth of gold certificates from Hochbrunn’s trunk. They split the certificates equally and cooked up a plan for her to send letters and telegrams to him about collecting rents.

Clara didn’t leave right away. In fact she waited six weeks to leave town.

Von Tobel disputed Clara’s version of what happened after the murder. He testified that he didn’t know anything about any gold certificates and claimed he didn’t know Hochbrunn was dead until the body was discovered.

A jury of eight men and four women acquitted Clara of the murder of Ferdinand Hochbrunn on January 13, 1923. “I surely wish the young woman all happiness in the future,” said one of the female jurors, whose tears had flowed freely during the defense counsel’s arguments. “She has surely seen enough of the seamy side of life. Now she may find peace and better things.”

Clara stayed in Seattle for a few months after the trial ended. In April she told a newspaper reporter that she’d left her job as a café hostess and planned to return to Oakland to live with friends.

Hochbrunn’s estate was estimated to be worth about $100,000. His will, if there was one, was never located. A business partner sued for half of the estate, but the court awarded the estate to his brother, Henry Hochbrunn. Henry died the day before the matter was settled. His children inherited their uncle’s estate.

After her comment about moving to Oakland, Clara Skarin disappeared without a trace.

Featured photo: news photo of Clara Skarin taken after her arrest, on September 9, 1922. Collection of the author.

I always have to wonder about female murderers getting acquitted in those days. What they did to get juries to sympathize with them. We’re too jaded these days, I think, to have let them off.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Not always—what about Casey Anthony? But it’s true that it used to be harder for people to imagine a woman being a murderer. Particularly if she was attractive.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I was surprised when I read that Clara was acquitted.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The jury believed the story about the sexual abuse, which, of course, could have been true and would have been a powerful motive for murder. I don’t know if they were told about the deaths of her mother and Mrs. Winborn. Apparently Clara was good at garnering sympathy!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I imagine the full facts of the case will never be known.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As rampant as sexual abuse of women and children is in 2021, it happened without comment in the very early 20th century. And then, just like today, everyone knew a woman or girl who had been molested, or interfered with.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It sounds like Clara was a sociopath. What a strange and twisted sequence of events.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed! She changed her name after the trial and became untraceable. I’d love to know what happened to her. Did she commit other murders? Thanks for commenting, Liz.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hmm. It wouldn’t surprise me if she did commit other murders.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It sounds like the jury viewed the killing as an act of self-defense. It may have been, but her fraudulent behavior afterward suggests the killing was premeditated. I’m surprised the jury didn’t convict her for stealing Hochbrunn’s money.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think you’re right about the jury believing Clara was acting in self defense. I don’t know if she was even charged with stealing the money. Thanks, Brad!

LikeLiked by 2 people