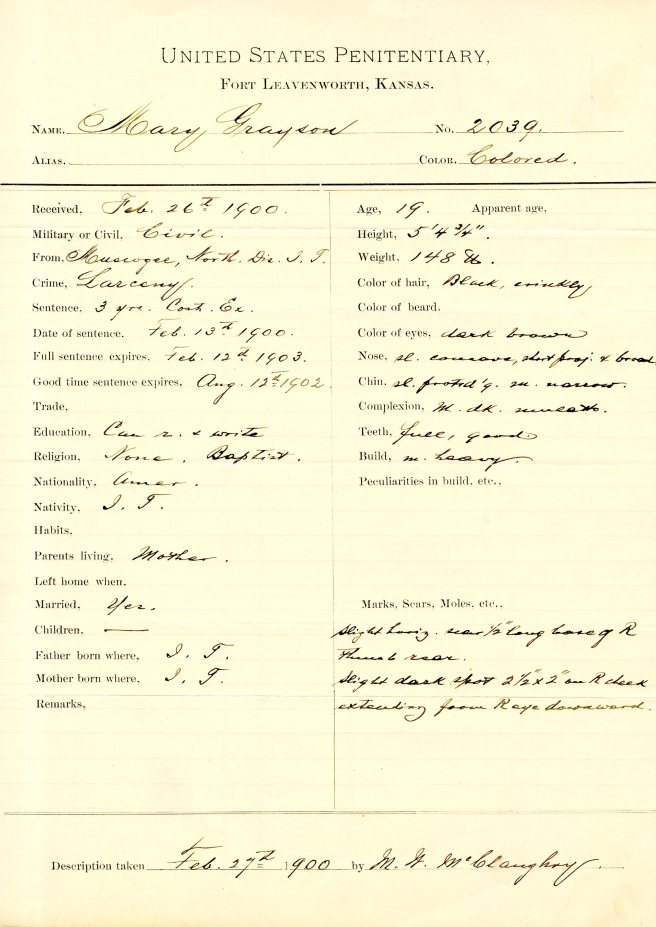

Mary Grayson, Mollie Martin and Louie Vann were charged with “robbing J. Teter at Tulsa.” The Claremore Commissioner’s Court in Indian Territory held them for a grand jury hearing on bond of $300 each. Of the three, only Mary Grayson was convicted of a crime: larceny. She was sentenced to three years in prison on February 13, 1900. Because the crime was committed on federal land (Oklahoma did not become a state until 1907), she was sent to serve her time at the newly-constructed Leavenworth Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

But Leavenworth had no housing for women. Mary and another federal prisoner, Mary Snowden, were transferred to the Kansas State Penitentiary in nearby Lansing on March 2, 1900.

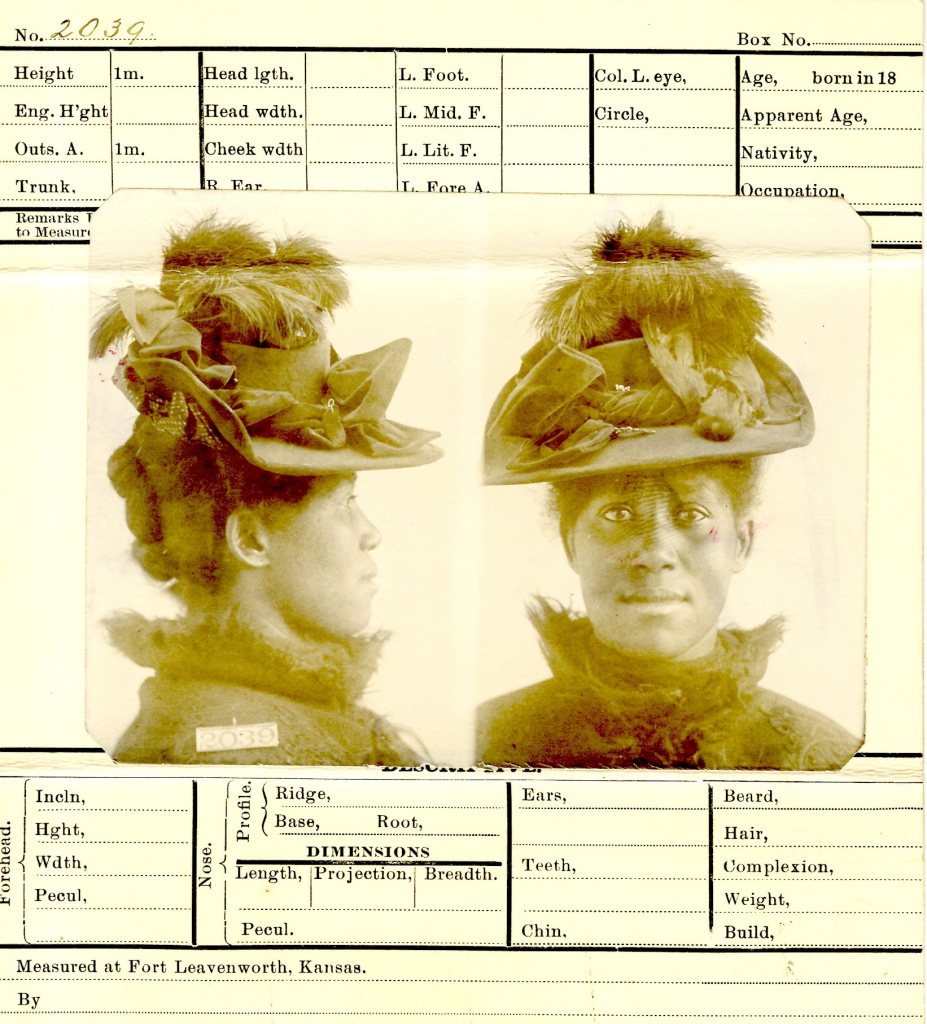

Her mugshots make it clear that Mary was a woman with a taste for the latest fashions. Her coat has a fur trimmed collar. And then there’s her hat. Decorated with velvet and satin ribbons, it has a stuffed bird reclining on the brim and an explosion of feathers emerging from the crown.

For a few years now I’ve been trying to answer this question: Who was Mary Grayson?

Her records from Leavenworth provide a brief story of her life. She was 19 years old when she went to prison. She was able to read and write. She wasn’t religious but she’d been raised a Baptist. She and her parents were born in Indian Territory. Her father, whose name was not recorded, was deceased. Her mother, Rose Steven, lived in Choska, I.T., a tiny community southeast of Tulsa.

A crucial detail revealed in her prison records is that Grayson was her married name—her husband was John Grayson of Tulsa. But Mary lived in Muskogee, so the couple, who had no children, were separated.

Four months after she arrived at the prison, the federal census was taken on June 18, 1900. Mary’s birth date was recorded by the census enumerator as “March 1881” and her marital status by then was “divorced.”

Grayson was a fairly common last name in Indian Territory, so gathering more information about Mary posed some challenges. Initially I mistook two other women for her.

The first woman I misidentified was the daughter of Daniel Grayson, a Creek Freedman. This Mary Grayson gave a deposition on June 7, 1900 to the Federal Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes at Atoka, I.T. (These cards are extremely valuable for anyone researching ancestors who were freedmen). The Mary Grayson sent to Leavenworth would not have been able to testify then because she was in prison. There are additional facts that don’t match: the woman who testified wasn’t married, she was 21 years old, and she had an infant son. According to other testimony provided to the commission, her father was alive in 1900.

The second Mary Grayson I confused with our stylish lady was Mary Ellen Grayson, née Hayes, a Black woman who was born in 1873 in Kansas and lived most of her life in Hutchinson, Kansas. In March 1909, she pulled a revolver from her skirt and shot at two women who were walking by her on the street. The press reported that the shooting stemmed from an argument over a man. The bullets missed, but Mary was arrested and charged with assault with intent to kill. Four years later, in April 1913, Mary was charged with running a bawdy house. In 1919 she was charged with having two quarts of wine in her home in violation of the state’s “bone dry” statute. The police seemed to have it in for Mary, however none of the charges against her stuck.

In 1914 Mary was granted a divorce from her husband, William S. Grayson, on grounds of abandonment, but she kept his surname. She died in 1963. The social security death index tells us that her mother’s name was Sophie J. Cavens and her father was Henry Hayes. Her birth year and place, date of divorce, husband’s first name and mother’s name are all wrong; She was not the Mary Grayson sent to Leavenworth.

Which brings us back to the Mary Grayson with the self-assured smile and remarkable hat. She was photographed at the Kansas State Penitentiary in April 1901. Hats weren’t allowed in these photos, but note the feather boa. Even in prison, the lady was stylin!

Depending on whether or not she earned “good-time,” Mary was released in either 1902 or 1903. I hope the jailers gave her back her hat when she left.

In 1905 a man named Garfield Williams married a woman named Mary Grayson in Carter, Oklahoma. Is this the right Mary? I’m not sure, and having been wrong twice, I’m being very careful. But I plan to keep digging to try and figure it out.

Keep digging, Shayne! We must see the wedding hat!

Dave Senay

Sent from my mobile device.

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

Haha! I’ll try, Dave!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great research and great mugshots! I especially like the second set because of her Devil-may-care smile.

LikeLiked by 4 people

She has a wonderful smile in the second set of photos! Thanks, Brad!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to the follow-up post. Will the REAL Mary Grayson please stand up?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have my fingers crossed for more info becoming available. Thanks, Liz!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re welcome, Shayne!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this story for several reasons. The photos are spectacular! If she wasn’t scared of prison, was she scared of anything or anyone? I run into the same challenges of people I’m researching with the same name. The first sheriff of Reno County, KS, was Charles Collins. Now, I’ve got to see if I can learn anything else about the Mary Grayson who lived in Hutchinson, KS. Love your blogs!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Jim! I’m enjoying your blog posts! Good luck with your research!

LikeLike

The Mary Grayson (1873-1963) who lived in Hutchinson had a grandson by the name of Chester Isaac Lewis, Jr. (1929-1990) who is famous in our part of Kansas. He was born in Hutchinson to a father (Sr.) who was editor of the Hutchinson Blade, an African American newspaper that attacked local practices of racial segregation. Junior battled segregation and inequality, attended the University of Kansas law school, was a leader in the Wichita NAACP, and mentored a group of youth who in 1958 organized the first sit-in to protest lunch counter segregation at the Dockum Drug Store. Hutchinson has a plaza/pocket park in his honor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is great info—I’ll tag him! Thanks for posting this, Jim!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. Chester Lewis wasn’t satisfied with only focusing on change through court action. As a leader of the “Young Turks,” he was supportive of non-violent protest. When the national NAACP wouldn’t reform, he resigned. Instead, he endorsed the Black Power Movement.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Just stumbled upon this entry Shayne and LOVED it. Thanks for fueling the flame.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Robin!

LikeLiked by 1 person